Chapter Four: Simple Compositions

4.1 The Rule of Thirds

The Golden Ratio

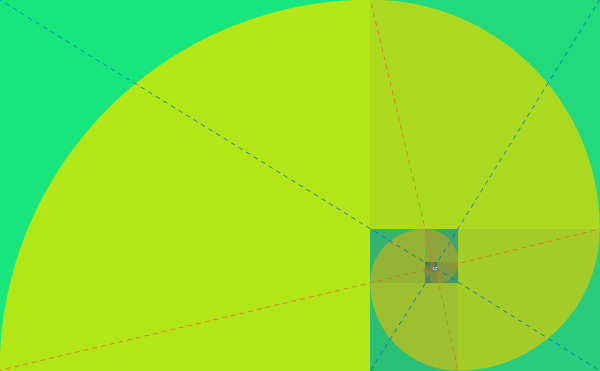

▲ Diagram illustrating the Golden Ratio.

The concept of the golden section was first explored by Pythagoras in ancient Greece, yet it was not until Euclid’s treatise *Elements* that a formal mathematical discourse on the subject emerged. The golden section arises from the golden ratio—a proportion rooted in mathematics, with values approximating 0.618 or 1.618. Revered for its inherent harmony and aesthetic grace, this ratio has long held a place in artistic composition. In photography, the golden section informs numerous compositional strategies; over time, these have been simplified into widely adopted techniques such as the rule of thirds and grid-based framing. The compositional methods discussed below all stem from this foundational principle.

▲ Many modern cameras offer grid overlays to assist in composition. By activating the rule of thirds guide on the viewfinder or LCD screen, photographers may align key elements along these intersecting lines to achieve balanced and dynamic framing.

Overcoming the Pitfalls of Central Composition

The rule of thirds employs a grid formed by four lines—two vertical and two horizontal—that divide the frame into nine equal rectangles. Their intersections create four focal points, serving as reference markers for placing primary subjects and guiding visual flow. When applied according to the golden ratio, these lines should be positioned at intervals corresponding to 0.618 or 1.618. If the total length C equals A + B, then C:(A+B) = A:B—a proportion that underlies the harmony of this structure. The rule of thirds thus represents a practical simplification of the golden section, functioning as a composite of vertical and horizontal thirds. By utilizing these points—or adhering to the principle of thirds—photographers may avoid the visual monotony often associated with central or symmetrical compositions. Placing a subject precisely at the center may render an image static and unengaging, diminishing narrative tension. Similarly, symmetrical arrangements, while powerful when intentional, can become predictable and visually fatiguing if applied without purpose. Yet neither central nor symmetrical composition is inherently flawed—each finds its place depending on context and subject. The rule of thirds, however, offers a proven path toward visual balance, rhythm, and aesthetic resonance.

► After spending five days in Queenstown, I journeyed to Wanaka—just over an

hour away. Known as the "smaller Queenstown," Wanaka boasts a serene alpine lake and an abundance of

water-based activities. Yet its most distinguishing trait lies in its quietude: fewer tourists, a slower

pace of life, and an atmosphere steeped in tranquility. I stayed only one night, yet the interplay of

lake and mountains left a lasting impression. Should opportunity arise again, I would gladly extend my

stay to truly immerse myself in the rhythm of this place.

Before dining at a modest local café, I

strolled along the lakeshore. It was already 7 p.m., yet twilight lingered, as if sunlight hesitated to

retreat. I saw a solitary figure seated on the bank, reading beneath an open sky framed by distant peaks

and shimmering water—so peaceful, so effortlessly beautiful. I composed the scene using the rule of

thirds, subtly emphasizing silhouette to evoke a sense of quiet contemplation.Nikon D300 & AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 G ED DX

► As in the previous image, this photograph also employs the rule of thirds. However, whereas the subject was positioned at the lower-right intersection in the earlier shot, here it is placed at the lower-left. The four focal points of the grid possess an inherent balance, and thus not every placement yields equal visual harmony. In this instance, the subject is reading a book facing left—thereby creating spatial directionality. Positioning him at the lower-right point provides visual space for his gaze to travel, enhancing narrative flow. Placing him at the lower-left point disrupts this balance: though space exists on his right, it lacks compositional weight. The result is a less cohesive image. Therefore, the earlier composition proves more effective in guiding the eye and sustaining visual equilibrium.Nikon D300 & AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 G ED DX

Balance and Spatial Continuity

Whether applying vertical or horizontal thirds, or combining both in the rule of thirds grid, attention must be paid to visual balance. For instance, when photographing elements in the sky, placing the subject at the upper-left or upper-right intersection often yields a more dynamic composition. Conversely, when capturing subjects grounded in terrain—such as people standing on earth—the lower-left or lower-right points generally provide greater stability and natural flow.

When a subject exhibits directional movement—such as looking, pointing, or gesturing—it is essential to reserve more space in the direction of motion. This creates visual continuity and prevents imbalance. Neglecting directional intent disrupts narrative coherence, weakening the emotional impact and structural integrity of the image.

◄ In Wanaka, after 6 p.m., the moon becomes visible in the twilight sky. Though seeing the moon during daylight is not uncommon, here it appears unusually bright and distinct—hanging above the landscape like a celestial witness to earthly beauty. I spotted this scene while driving, stopped at a suitable vantage point, and composed the image through the car window using the rule of thirds. I selected a sunlit slope, a shadowed road surface, grazing sheep on the hillside, and a long, drifting cloud—all framed to reflect the moon’s presence. To emphasize context over detail, I widened the frame despite reducing the moon’s prominence. The resulting composition—where light and shadow converse with celestial presence—I found deeply compelling.Nikon D300 & AF-S VR Zoom-Nikkor 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 G ED DX

The Four Intersections and the Grid

Initially, I used only the four intersection points of the rule of thirds grid as reference for subject placement. Over time, however, I shifted toward a more flexible approach: employing one-third divisions of the frame’s width and height as compositional guides. This method allows for greater variety in spatial arrangement, freeing the photographer from rigid adherence to fixed points and enabling more organic, expressive compositions.